Have you ever wondered why some organizations seem to deliver slowly, cost a fortune, and leave customers feeling less than delighted? It is because the complex interactions between organizational units can create delays and feedback loops that are difficult to oversee, making it a daunting task to understand why you are not getting the results expected.

Systems Thinking supports you with a holistic approach to problem-solving that seeks to understand the entire system, instead of simply addressing the individual parts of a system. By recognizing the intricate relationships between different components, it becomes easier to grasp how changes to one part of the system can impact the entire operation. So if you want to improve globally by designing a system that truly delights your customers, it’s time to take a step back and see the bigger picture with Systems Thinking.

Feedback loops and Delays Impede Learning

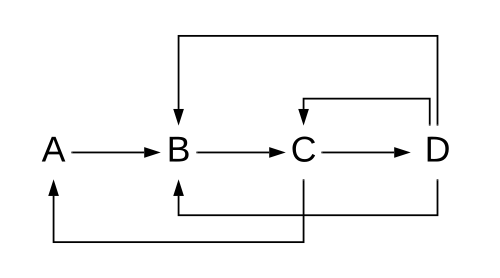

One of the key principles of Systems Thinking is the recognition of feedback loops. These interconnections between different elements within a system create a reciprocal relationship. Changes in one unit of an organization can affect the performance of other units, which in turn can impact the original unit.

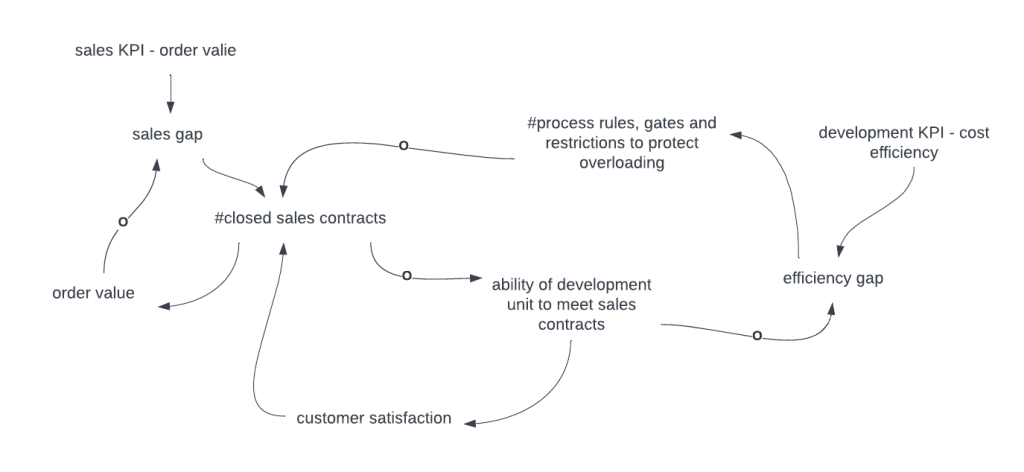

For example, the sales department closes sales contracts to meet its targets. In doing so it closes more sales contracts than the development unit can deliver. This in turn makes the development unit deliver late, and customer confidence drops which in turn makes it harder for the sales to close new contracts. The development unit might also introduces extra rules and process steps to meet its own cost goals slowing the whole process down even further. Pressure from sales goals, might force the development unit to take on new work even though it is already overloaded, etc.

Figure 1. Feedback loops

Frequently, the feedback of decisions within organizations is impeded or significantly slowed down due to a disrupted feedback loop. In consequence, learning at the system level is problematic. Peter M. Senge, an American systems scientist and the author of the seminal book Fifth Discipline, speaks about a limited “decision horizon,” where people have a narrow horizon to observe the effects of their decisions. People end up fixing problems locally and, at the same time, degrade the situation for their colleagues. And even worse, they are unable to learn from their mistakes.

“When our actions have consequences beyond our learning horizon, it becomes impossible to learn from direct experience”

—Peter Senge

Consider a scenario where a team is solely responsible for developing a specific component of a product. In such cases, it can be challenging for them to comprehend the impact of their decisions on other teams. This holds true for technical teams such as the ‘iOS team’ as well as non-technical teams like business analysts. Despite their best intentions, their decisions might be doing more harm than good for the organization.

By recognizing these feedback loops, organizations can design systems that are self-correcting and adaptive. This can lead to a more resilient and flexible organization that is better equipped to respond to changing circumstances.

System Thinking For Organization Design

Organization design is a complex and dynamic process that requires a thorough understanding of the interrelationships between different elements within an organization. This is where Systems Thinking can play a crucial role. When applied to organization design, Systems Thinking can help organizations better understand the relationships between different departments, processes, and people.

To design an organization there are three topics from Systems Thinking to benefit from.

1st: Chronic problems result from system structure

In organisations, systems structure includes information flow, how people make decisions and take actions. That is the complex interactions of people driven by the organization’s roles, responsibilities, division of work and measures of success. The recurring problems we observe are generated by the system’s structure. Yo get a deeper insight into this structure you can use Causal Loop Diagrams (CLD).

Below is an example CLD showing the sales-development dynamics described above.

Figure 2. A Sales-Development dynamic

This CLD describes how the elements of the sales-development system form the complex interactions that generate the observed results.

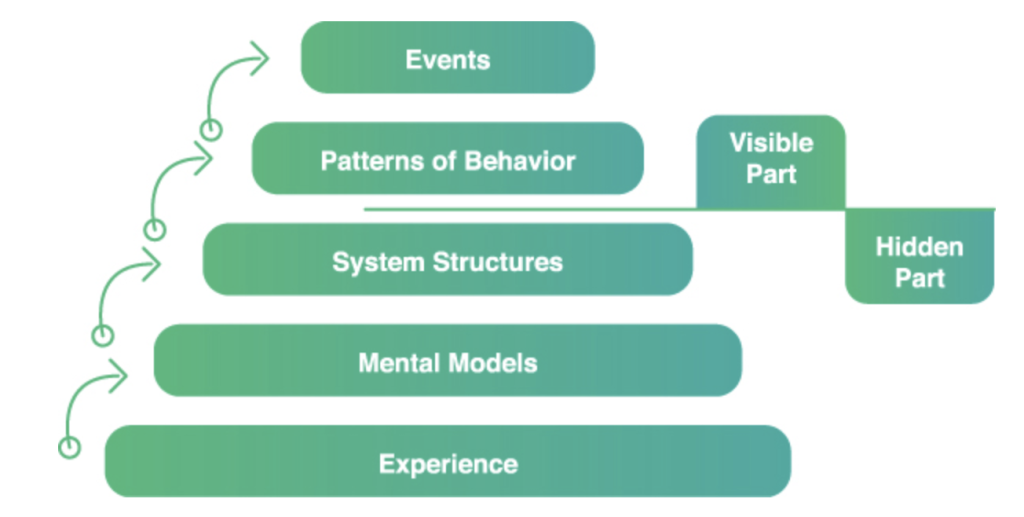

The System Structure Generates the Patterns of behaviour

The system structure shapes the sustained patterns of behaviour in companies. They contribute a lot to what we call a “culture.” The figure below illustrates how experience, mental models, system structures, patterns of behaviour, and events are connected in a model called the iceberg of systems thinking.

Figure 3. Iceberg of systems thinking.

Separate, unrelated incidents are called events. Behaviour that is consistently demonstrated three times or more is called a pattern. Organizational structures generate the patterns and are the product of the mental models of their constructors—that is to say, of the designers of the organizations. They reflect what those designers believe about how the world works.

You get what you design for…

Organizations are perfectly designed to achieve the results they are achieving right now. And the irony is that the people that designed the system to produce the unwanted results are the same people that prevent it from improving. To quote Walt Kelly:

“We have met the Enemy and he is us”.

—Walt Kelly

So what are the critical leverage points for change?

By changing the structure of your system, you can create new patterns and observe the outcomes you seek of. But how do you go about making these changes? From an organizational design perspective, there are three key leverage points to consider.

Firstly, take a closer look at your information flows. Dysfunctions in your system often stem from a lack of communication and information sharing. By redesigning your information flows and adding new feedback loops, you can provide critical information to the parts of your system that need it most, leading to improved outcomes.

Secondly, examine the rules, incentives, and constraints of your units. Your system’s rules define its boundaries, scope, and degree of freedom. Changing these rules can have a significant impact on your system’s behavior. Understanding your system’s rules is crucial to designing effective interventions that will boost its performance.

Finally, consider redesigning the purpose of your units. When senior management redefines the purpose or goals of units, it can drive people in a whole new direction of behaviors. Imagine the impact of redefining the goals of your product group, for example.

2nd: The System cannot be divided into separate parts

Each organization unit has a purpose or function within the larger organization. From an organisational design perspective, we define the purpose of a product group, usually a Value Proposition or Mission statement. Then identify all essential parts such as teams required to fulfil that purpose and group them into a product group. Once all the parts are identified we then begin the design of the whole group by improving the teams and their interactions only if it also improves the whole.

Include Essential parts

For a product group to fullfill its purpose or function all its essential parts are required. A team is an essential part of a product group if the product group cannot fulfil its purpose without that team and so on. The programmer in a software development team is an essential part, if without that skill the team could not fulfil its purpose of delivering a working product increment. A database component is an essential part of a software system if without it the system can no longer achieve its purpose of offering features to its users. So, if you want to be adaptable at the level of a product group while delivering highest value you need to consider all essential parts and include them into your product group.

Famous systems thinker Prof Russell Ackoff makes it very clear.

A system is a whole that cannot be divided into independent parts without the loss of its essential properties or functions.

—Russel Ackoff

3rd: The performance of a System depends on how the parts interact

The performance of a system depends on how the parts are tuned, not on how they perform separately. The same applies to the units in your organization.

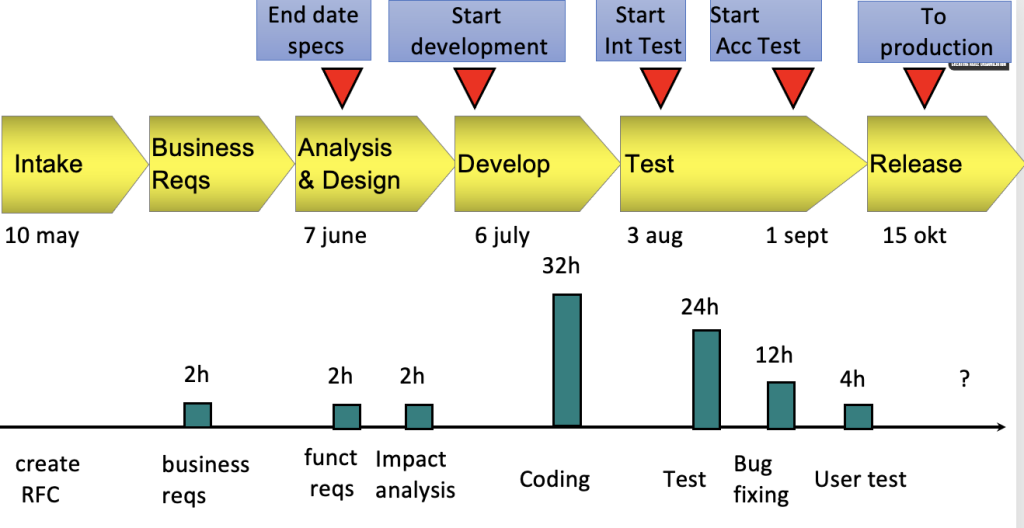

For example, below you can see a Value Stream map (from a financial company) that shows the time it took from the creation of a Request For Change (RFC) on May 10, to its delivery into production on October 15. The map also shows that each individual activity was done very efficiently by a separate teams such as Analysis and Design, Develop, and Test.

Although each of these teams was efficient locally, the performance of the larger group was poor. Or as Ackoff states

When the performances of the parts of a system, considered separately, are improved, the performance of the whole may not be (and usually is not) improved.

—R. Ackoff

Therefore, when designing your organization consider the three Rules

- Rule One: If you optimize a system, you will sub-optimize one or more components.

- Rule Two: If you optimize the components of a system, you will sub-optimize the system.

- Rule Three: The components of a system form subgroups that obey Rules One and Two.

So, avoid optimising all individual teams, persons or departments, but intead understand that to improve a team, product group or organization you will sub optimise one or more its its parts.

Management Implications

You need to redesign so that all the activities and skills required to fulfil the purpose or mission are contained within the product group. Then improve that product group by moving from local to global product group optimization.

In conclusion

Systems Thinking is one of the key concepts required for Creating Agile Organizations. It provides a valuable approach to organization design that can help organizations better understand the interrelationships between different elements within the system. By recognizing feedback loops and boundaries, organizations can design systems that are more efficient, effective, and resilient.